Home | FAQ

The process by which money is created is so simple

that the mind is repelled.

Where something so important is involved,

a deeper mystery seems only decent

- John K. Galbraith

Money: Whence It Came, Where It Went, 1975

- Context

- Wasn't the trillion dollar coin idea originally about providing everyone with $2000 per month COVID emergency relief?

- Doesn't this stretch the law beyond its original intent?

- Logistics

- Why platinum coins?

- Does this require a lot of platinum?

- Where does the platinum come from?

- What will the coins look like?

- Where will the coins be kept?

- What if the coins are stolen?

- Accounting

- What is seigniorage?

- Does this add to the national debt?

- Does this reduce the deficit?

- Is this an accounting gimmick?

- Economics

- Is this "printing money"?

- Is this hyperinflationary?

- If we can do this, why not give everyone unlimited money?

- If we can do this, why tax at all?

- Institutional Politics

- Is this monetary policy?

- What role does the Federal Reserve play?

- What does the Federal Reserve do with the coins?

- Does this affect Federal Reserve remittances to the Treasury?

- Does this undermine Federal Reserve independence?

- Strategy

1. Context

1a. Wasn't the trillion dollar coin idea originally about providing everyone with $2000 per month COVID emergency relief?

No. The #MintTheCoin hashtag was first used in 2011 in reference to the current proposal for the Treasury Secretary to unilaterally exercise their authority to mint platinum coins under 31 U.S.C. § 5112(k) in order to avert a debt ceiling crisis. For more historical context, click here.

Rep. Tlaib's #ABCAct, first announced on March 21, 2020, is a standalone legislative initiative. It proposed using platinum coin seigniorage to fund a "money-financed fiscal program" that would have provided direct emergency cash relief to every person in America, as part of a broader response to the COVID-19 pandemic. For more information, see the #ABCAct website here.

1b. Doesn't this stretch the law beyond its original intent?

Yes and no.

One of the original co-authors of 31 U.S.C. § 5112 was Rep. Michael Castle (R.-Del.), who at the time was the Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Domestic and International Monetary Policy, which had jurisdiction over matters related to coinage.

According to Rep. Castle, his goal in introducing the provision:

In Rep. Castle's opinion, authorizing the Treasury Secretary to mint high value (i.e. trillion-dollar) coins was not:[W]as to enable the Treasury to put out collectable platinum coins of a variety of sizes...[in order to] produc[e] income from seignorage...as a means of reducing the deficit, albeit by a small amount, without raising taxes or cutting spending.

"We saw it as an opportunity to make money for the Mint and the Treasury," he remembers.

However, according to the other original co-author of the provision, Philip Diehl, who at the time was the Director of the U.S. Mint:[T]he intent of anything that I drafted or that anyone who worked with me drafted...[It] is a stretch beyond anything we were trying to do.

According to Willamette Law Professor Rohan Grey:When I first heard about the idea to mint a trillion-dollar coin, I was very surprised.

But because I know that law backwards and forwards, I knew immediately that the guy who came up with the idea was right.

...What is unusual about the law (31 U.S.C. § 5112(k)) is that it gives the Secretary complete discretion regarding all specifications of the coin, including denominations.

...When we passed this law in 1996, it was with full knowledge that it was unprecedented in the history of US coinage.

[Until then] Congress had always specified coin denominations by law.

...[31 U.S.C. § 5112(k)] provides Treasury all necessary authority to [issue $1 trillion coins]. I know this because I wrote the law and produced the nation’s first platinum coin.

I’ve been through the entire process.

...Yes, this is an unintended consequence of the platinum coin bill, but how many other pieces of legislation have had unintended consequences? Most, I’d guess.

Furthermore, according to Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Tribe:Plenty of statutes have been reinterpreted over time, particularly in moments of crisis.

In 2008, for example, the Fed justified its unprecedented expansion of emergency lending facilities, including...purchases of assets with limited market value, under the auspices of Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, despite little evidence that that provision was enacted with such use in mind.

Additionally, as Diehl notes:[It does not make] sense to think about [minting trillion-dollar coins] as some sort of “loophole” issue.

Using the statute this way doesn’t entail exploiting a loophole; it entails just reading the plain language that Congress used. The statute clearly does authorize the issuance of trillion-dollar coins.

First, the statute itself doesn’t set any limit on coin value.

Second, other clauses of 31 U.S.C. § 5112 do set such limits, but § 5112(k) — dealing with platinum coins — does not. So expressio unius strengthens the inference that there isn’t any limit here.

Of course, Congress probably didn’t have trillion-dollar coins in mind, but there’s no textual or other legal basis for importing this probable intention into the statute.

What 535 people might have had in their collective “mind” just can’t control the meaning of a law this clear.

It’s also quite clear that the minting of such a coin couldn’t be challenged; I don’t see who would have standing.

More broadly, as Grey notes:Any court challenge is likely to be quickly dismissed since:

- authority to mint the coin is firmly rooted in law that itself is grounded in the expressed constitutional powers of Congress,

- Treasury has routinely exercised this authority since the birth of the republic, and

- the accounting treatment of the coin is...identical to the treatment of all other coins.

...When the Mint ships a coin from its vaults to those of the Fed, it books as profit (or “seigniorage”) an amount equal to the difference between the coin’s face value and its cost of production.

This amount is subsequently transferred to the general fund of the treasury where it is available to...finance government operations just like with proceeds of bond sales or additional tax revenues.

The same applies for a quarter dollar.

In 2019, for example, the Mint transferred $540 million in seigniorage revenue to the Treasury's general operating account.Seigniorage has been a valid and legal method of increasing the Treasury’s fiscal capacity for centuries.

The same year, the Federal Reserve remitted $54.9 billion in surplus income to the Treasury's general operating account.

Although not recorded as such for accounting purposes, Federal Reserve remittance income is functionally the same as seigniorage revenue, since it derives from the Federal Reserve Systems's Congressionally-delegated power to create money.

As the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit noted in 2019:

[Federal Reserve Banks] are the issuers of base money. They do not lend out preexisting funds; they create “funds” in the most elemental sense. They perform this function on behalf of the United States, as federal instrumentalities.

...Congress has provided that the net earnings of the [Federal Reserve Banks] be “recorded as revenue by the Department of Treasury,” ...and the [Federal Reserve Banks] are required to remit all their excess earnings to the United States Treasury[.]

...[Furthermore,] as the United States explains, “in the event that a [Federal Reserve Bank] is liquidated, any value remaining (after debts are paid and certain required payments are made)...become[s] the property of the United States[.]" (citing 12 U.S.C. § 411).

Accordingly, a bank’s failure to pay the applicable amount of interest on a loan from a [Federal Reserve Bank] injures the public fisc.

...[M]oney created for [Federal Reserve emergency lending programs is] as much a product of the “public fisc” as money that is distributed by the Treasury Department.

2. Logistics

2a. Why platinum coins?

31 U.S.C. § 5112 of the Coinage Act gives the Treasury Secretary the discretionary authority to mint and issue coins containing a wide range of metals, including copper, zinc, silver, gold, palladium, and platinum.

There is no statutory or constitutional limit on the quantity of coins that the Treasury Secretary may issue.

However, most coins have strict limits on the denominations (face value amounts) that can be minted, i.e. a nickel, dime, quarter, half-dollar, dollar, or twenty-dollar coin.

In contrast, there is no limit on the face value of platinum coins that can be issued under 31 U.S.C. § 5112(k).

As former Mint Director Philip N. Diehl, who drafted 31 U.S.C. § 5112(k), noted,

Consequently, it is logistically much simpler for the Treasury Secretary to issue a small number of high value platinum coins, i.e. $1 trillion each, than to issue hundreds of thousands or millions of other smaller denomination coins.When we passed this law in 1996, it was with full knowledge that it was unprecedented in the history of US coinage.

[Until then] Congress had always specified coin denominations by law."

2b. Does this require a lot of platinum?

No. This is a common misconception.

The face value of coins issued by the U.S. Treasury are determined by legal tender law, not the bullion value of the metal used to make them.

This is consistent with the broader principle of nominalism, which has been the basis of Western monetary law for over four centuries.

In particular, 31 U.S.C. § 5112(k) authorizes the Treasury Secretary to mint and issue platinum coins "in accordance with such specifications...[and] denominations...as the Secretary, in the Secretary’s discretion, may prescribe from time to time."

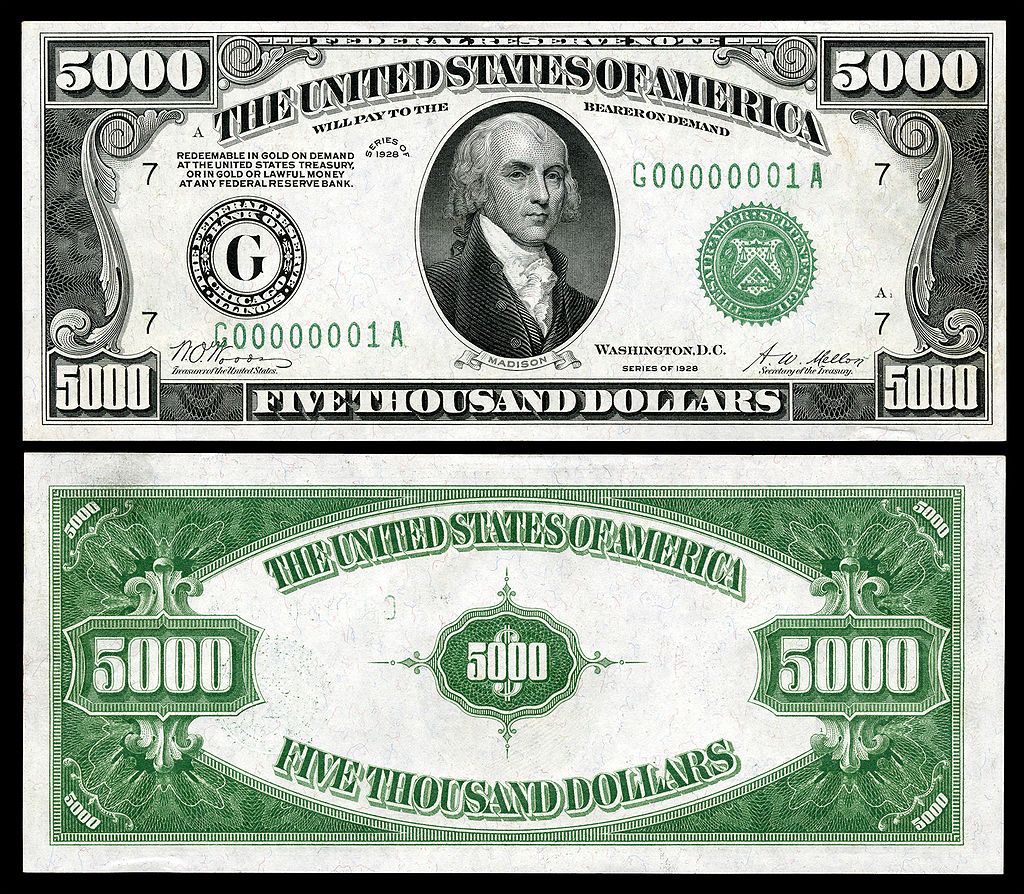

Consequently, a $1 trillion platinum coin does not need be any larger than a regular-sized coin. For example:

2c. Where does the platinum come from?

The U.S. Mint at West Point already possesses a more-than-adequate stock of platinum, which it presently uses to issue proof and bullion coins with face values of up to $100 that it sells to investors and collectors.

2d. What will the coins look like?

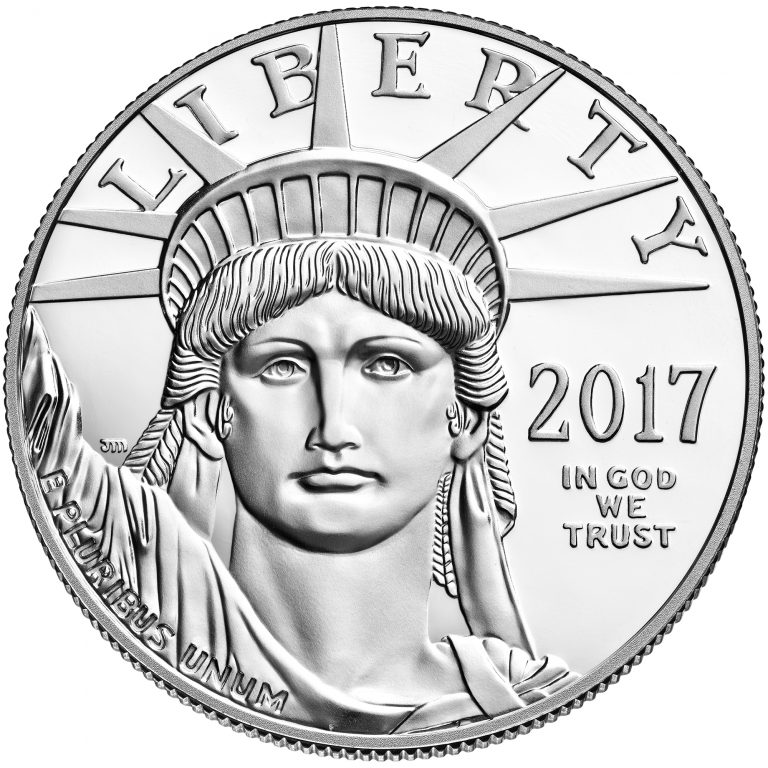

Currently, platinum coins issued by the U.S. Mint have this design:

However, 31 U.S.C. § 5112(k) authorizes the Treasury Secretary to mint and issue platinum coins "in accordance with such...designs, varieties...and inscriptions as the Secretary, in the Secretary’s discretion, may prescribe from time to time."

Over the years, members of the public have come up with many creative and amusing design proposals for the $1 trillion coin.

2e. Where will the coins be kept?

Once the U.S. Mint deposits the coins, they become the property of the Federal Reserve System.

The Federal Reserve could store the coins in its gold vault, located in the basement of the Manhattan building of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, or at the Marriner S. Eccles building in Washington D.C., across the road from the U.S. Treasury, where the offices of the Fed's Board of Governors are located.

Alternatively, the Federal Reserve could make the coins available for public display as part of the Smithsonian's National Numismatic Collection at the National Museum of American History.

2f. What if the coins are stolen?

While the theft of a trillion dollar currency instrument is an amusing premise for an episode of a television show, there is little risk of it actually occurring.

As former U.S. Mint Director Philip Diehl notes:

Instead, as Jim Halpern, co-chairman of collectibles company Heritage Auctions notes, only a:Anyone who got their hands [on] a trillion-dollar coin couldn’t do very much with it...It would stand out to every bank and vendor in the country, and no one would accept it.

Doctor Evil-type collector would be interested in buying it for a few million dollars at most, if only to own something so illicit.Even then, however, as Sarah Mitroff notes:

[P]eddling high-profile stolen goods is far from easy.

...[A]t an auction the rare coin could fetch at least its value in platinum and up to several hundred thousand dollars...but only if the buyer could legally own it.

Which you can't.

3. Accounting

3a. What is seigniorage?

According to the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board, Seigniorage is:

[T]he face value of newly minted coins less the cost of production (which includes the cost of the metal, manufacturing, and transportation).Although this description focuses on coins, any monetary instrument whose face value exceeds its production cost can generate accounting profits from seigniorage.

It results from the sovereign power of the Government to directly create money and, although not an inflow of resources from the public, does increase the Government's net position in the same manner as an inflow of resources.

However, an excessive focus on the accounting treatment of monetary instruments can distract from the more important underlying legal dynamics, which stem from the "sovereign power of the Government to directly create money" referred to above.

As the Supreme Court noted in 1935:

Public law gives to...coinage a value which does not attach as a mere consequence of intrinsic value. Their quality as a legal tender is an attribute of law aside from their bullion value.Similarly, as John Maynard Keynes noted in 1930:

They bear therefore the impress of sovereign power which fixes value and authorizes their use in exchange.

The State...comes in first of all as the authority of law which enforces the payment of the thing which corresponds to the name or description in the contracts.While it may seem counterintuitive, all forms of public money - even money issued in previous eras under a "gold standard" - represent a kind of liability or debt of the government, in the sense that the government "promises" to receive it back in payment of debts owed to it.

But it comes in double when, in addition, it claims the right to determine and declare what thing corresponds to the name, and to vary its declaration from time to time - when that is to say, it claims the right to re-edit the dictionary.

This right is claimed by all modern states and has been so claimed for some four thousand years at least.

Thus, as British diplomat Alfred Mitchell-Innes noted in 1913:

[T]he general impression is that the only effect of transforming...gold into coins [under a gold standard regime] is to cut it into pieces of a certain weight and to stamp these pieces with the government mark guaranteeing their weight and fineness.

But is this really all that has been done? By no means.

What has really happened is that the government has put upon the pieces of gold a stamp which conveys the promise that they will be received by the government in payment of taxes or other debts due to it.

By issuing a coin, the government has incurred a liability towards its possessor just as it would have done had it made a purchase—has incurred, that is to say, an obligation to provide a credit by taxation or otherwise for the redemption of the coin and thus enable its possessor to get value for his money.

In virtue of the stamp it bears, the gold has changed its character from that of a mere commodity to that of a token of indebtedness.

In England the Bank of England buys the gold and gives in exchange coin, or bank-notes or a credit on its books.

In the United States the gold is deposited with the Mint and the depositor receives either coin or paper certificates in exchange.

The seller and the depositor alike receive a credit, the one on the official bank and the other direct on the government treasury.

The effect is precisely the same in both cases.

The coin, the paper certificates, the bank-notes and the credit on the books of the bank, are all identical in their nature, whatever the difference of form or of intrinsic value.

A priceless gem or a worthless bit of paper may equally be a token of debt, so long as the receiver knows what it stands for and the giver acknowledges his obligation to take it back in payment of a debt due.

Money, then, is credit and nothing but credit.

A's money is B's debt to him, and when B pays his debt, A's money disappears.

This is the whole theory of money.

3b. Does this add to the national debt?

No.

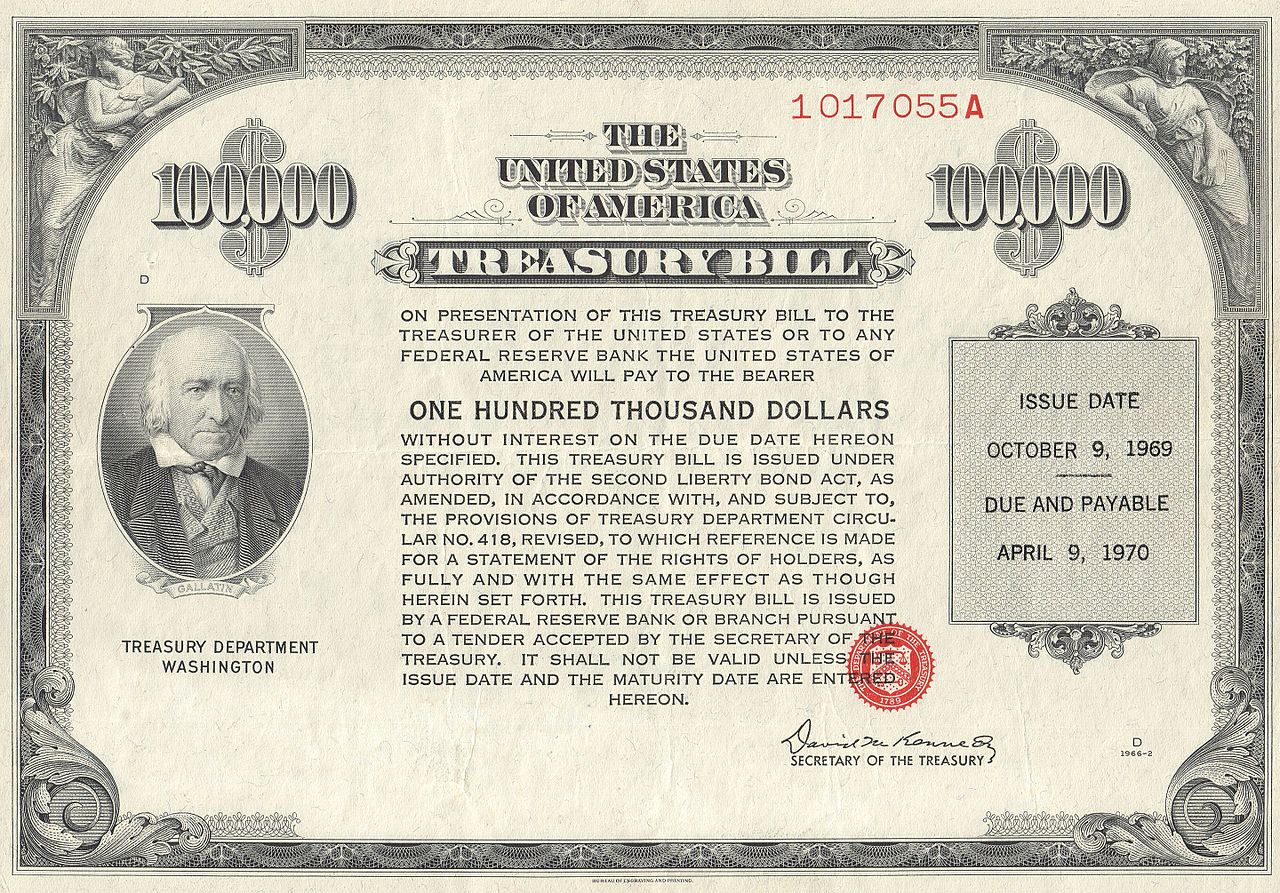

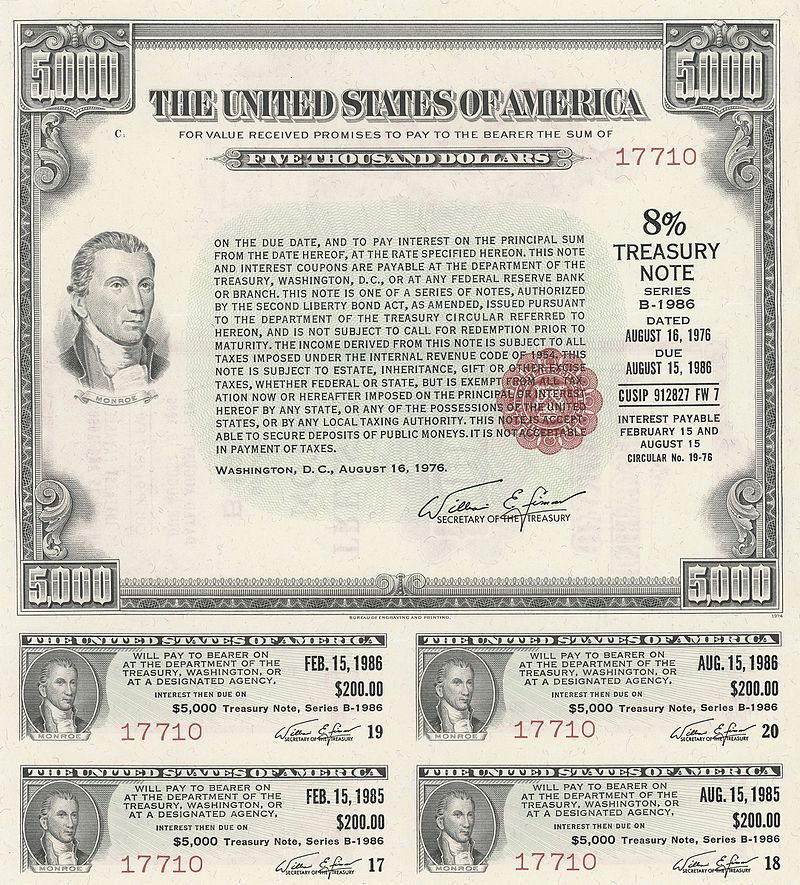

Public debt subject to limit under the debt ceiling, also known as the "national debt," is comprised of Treasury bonds, notes, bills and certificates of indebtedness, savings bonds and savings certificates, retirement and savings bonds, tax and loss bonds, and any other obligations "whose principal and interest are guaranteed by the United States Government," such as mortgage-backed securities issued by the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae).

Coins are not and have not ever been included in calculations of the national debt.

Other forms of non-interest bearing legal tender, such as Federal Reserve Notes and United States Currency Notes, are also not included in calculations of the national debt.

However, they are still considered "obligation[s] or other securit[ies] of the United States" under 18 U.S. Code § 8, along with Treasury bonds, bills, notes, and certificates of indebtedness.

More broadly, from an economic perspective, all public money is best understood as an obligation, liability, or debt of the issuing government, in the sense that the government promises to accept it back in payment of taxes or debts owed to it.

As British diplomat Alfred Mitchell-Innes noted in 1913:

By issuing a coin, the government has incurred a liability towards its possessor...that is to say, [it has incurred] an obligation to provide a credit by taxation or otherwise for the redemption of the coin and thus enable its possessor to get value for his money.Alternatively, modern U.S. public debt can also be understood as a special form of money itself.

... A priceless gem or a worthless bit of paper may equally be a token of debt, so long as the receiver knows what it stands for and the giver acknowledges his obligation to take it back in payment of a debt due.

As Thomas Edison observed in 1921:

Similarly, British economist John Maynard Keynes noted in 1937:If our nation can issue a dollar bond, it can issue a dollar bill. The element that makes the bond good makes the bill good also...

It is absurd to say that our country can issue $30,000,000 in bonds and not $30,000,000 in currency. Both are promises to pay...If the currency issued by the Government were no good, then the bonds issued would be no good either...

If the Government issues bonds, the brokers will sell them. The bonds will be negotiable: they will be considered as gilt-edged paper. Why? Because the Government is behind them, but who is behind the Government? The people.

Therefore it is the people who constitute the basis of Government credit.

[W]e can draw the line between “money” and “debts” at whatever point is most convenient for handling a particular problem.Furthermore, as economist Paul Krugman noted in 2013:

For example, we can treat as money any command over general purchasing power which the owner has not parted with for a period in excess of three months, and as debt what cannot be recovered for a longer period than this[.]

...[O]r we can substitute for “three months” one month or three days or three hours or any other period; or we can exclude from money whatever is not legal tender on the spot.

It is often convenient in practice to include in money...even such instruments as...treasury bills.

[When interest rates on short-term debt and money are identical,] issuing short-term debt and just ‘printing money’...are completely equivalent in their effect, so even huge increases in the monetary base...aren’t inflationary at all.Thus, as Willamette Law Professor Rohan Grey noted in 2019:

[F]or monetarily sovereign nations like the United States, the act of issuing government-backed securities [public debt], denominated in the domestic unit of account, which can be redeemed only for other government obligations [currency] also denominated in that unit of account, is functionally closer to “money creation” than it is to “borrowing.”Consequently, as former Senate Budget Committee Chief Economist (Democratic Staff) Stephanie Kelton & University of Missouri-Kansas City Economics Professor Scott Fullwiler noted in 2013:

This view is further supported by the fact that the Fed regularly adjusts the relative stock of circulating government securities vis-a-vis its own reserve liabilities as it deems appropriate for the conduct of monetary policy, without concern for one being “money” and the other being “debt.”

[Moreover, the Treasury and Fed coordinate closely to ensure that the private sector has sufficient reserves to purchase any and all Treasury securities offered at auction.]

...[M]ost people don’t get a loan from a bank by walking in and handing them a bag of cash so that the bank can lend it right back to them.

[T]he main advantage of [money-financed fiscal policy] is not that it provides a greater boost to the monetary base but that it would relieve the government from the practice of selling bonds altogether.

In other words, the main advantages of direct money creation are political rather than economic.

3c. Does this reduce the deficit?

No.

As the Government Accountability Office noted in 2004:

The profit earned from making coins, or seigniorage...is not counted as revenue in calculating the deficit or surplus for the annual budget.This makes sense, since the "deficit" is merely an accounting record of the total difference between government spending and taxation in any given period.

...[Instead,] [t]he issuance of coins results in an avoidance of government borrowing.

As Stephanie Kelton, former Chief Economist on the Senate Budget Committee (Democratic Staff), noted in 2017:

Government spending adds new money to the economy, and taxes take some of that money out again. It’s a constant churning of pluses and minuses, and their minuses become our pluses.

When the government spends more than it gets in taxes, a “deficit” is recorded on the government’s books. But that’s only half the story.

A little double-entry bookkeeping paints the rest of the picture.

Suppose the government spends $100 into the economy but collects just $90 in taxes, leaving behind an extra $10 for someone to hold. That extra $10 gets recorded as a surplus on someone else’s books.

That means that the government’s -$10 is always matched by +$10 in some other part of the economy. There is no mismatch and no problem with things adding up.

Balance sheets must balance, after all. The government’s deficit is always mirrored by an equivalent surplus in another part of the economy.

The problem is that policy makers are looking at this picture with one eye shut. They see the budget deficit, but they’re missing the matching surplus on the other side.

And since many Americans are missing it, too, they end up applauding efforts to balance the budget, even though it would mean erasing the surplus in the private sector.

... Congress can always create more room in the budget...to put more [financial] resources into education, infrastructure, defense and so on. It is purely a political decision.

Of course, there are real limits to what can be done. No country can commit to large-scale infrastructure investment unless it has the available labor, machinery, concrete and steel.

Trying to spend too much will cause an inflation problem.

The trick is to adjust the budget to make efficient use of the people, factories and raw materials we have.

But all of this goes unrecognized on Capitol Hill, where the very words “debt” and “deficit” have been weaponized for political ends.

They serve as body armor to politicians who would deny resources to struggling communities or demand cuts to popular programs.

...In a more rational world, lawmakers would...recognize that the risk of overspending is inflation, not bankruptcy.

They would avoid fruitless battles over the debt ceiling, and they would acknowledge that the deficit itself could be deployed as a potent weapon in the fights against inequality, poverty and economic stagnation.

3d. Is this an accounting gimmick?

Yes and no.

According to Willamette Law Professor Rohan Grey:

On one hand, using § 5112(k) to [mint and issue trillion-dollar coins] is clearly...an accounting “gimmick”[.]Indeed, as Matt Phillips at the New York Times notes:

...On the other...the fact that [it is] an accounting gimmick is a source of its strength, rather than a weakness.

Accounting workarounds are used regularly in financial and business contexts to overcome otherwise incoherent or suboptimal operating requirements that do not implicate a deeper economic or solvency issue.

...Indeed, the [concept of government "borrowing" and the debt ceiling itself] can be viewed as one big, poorly designed accounting gimmick, in that [they are] not intrinsically tied to any underlying real economic constraint, and [do] not impose any spending limitations not already inherent to the appropriations process.

...In that respect, the idea of “fighting an accounting problem with an accounting solution” is entirely coherent.

Nobody knows exactly how much the [Coronavirus] relief bill will add to the national debt; it was cobbled together so quickly that there wasn’t time for the Congressional Budget Office to carry out an analysis, though one is expected to be published this week.Furthermore, as Nathan Tankus notes:

But the Fed will be the biggest buyer by far of the bonds the government will sell to fund this spending.

Goldman Sachs analysts estimate the Fed will buy $2.4 trillion in Treasury securities as part of its recently reintroduced bond-buying programs. Economists at Morgan Stanley put the number at around $2.5 trillion in 2020 alone, rising to as much as $3 trillion for the entirety of the bond-buying program.

But the Fed isn’t an ordinary bondholder: By law, it has to pay its profits to the Treasury.

That means when the Treasury makes payments on bonds held by the Fed — either paying interest or paying it off at maturity — almost all the money eventually moves back to the Treasury.

When a government bond is involved, the cash moves from one government pocket to another.

[A]ccounting gimmicks are already at the center of the Stimulus Bill[.]Thus, as Scott Ferguson notes:

...454 billion of the reported 2 Trillion dollars [in the CARES Act of 2020] is going to [the Treasury's Exchange Stabilization Fund in order to]:[M]ake loans and loan guarantees to, and other investments in, programs or facilities established by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.This is an accounting gimmick. Yet Larry Kudlow (director of the National Economic Council) points to it as one of the most important provisions in the bill[:]And finally, I want to mention, the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund. That will be replenished.This accounting gimmick is far more dangerous than the platinum coin because it conceals what is going on to the public rather than reveals it.

It’s important, because that fund opens the door for Federal Reserve firepower to deal a broad-based way throughout the economy for distressed industries, for small businesses, for financial turbulence.

You’ve already seen the Fed take action. They intend to take more action. And in order to get this, we have to replenish the Treasury’s Emergency Fund.

It’s very, very important; not everybody understands that.

[T]he gambit of the coin is to make a spectacle out of really any financial instrument that is backed by the government[.]Morevoer, as Grey notes:

Not that I would read #MintTheCoin as purely making a mockery because I think it has positive value and significance as a way of galvanizing political movements.

So, I don’t want to say it’s just parodic, but I think it’s important to point out the parodic dimension of the gesture because it exposes the fact that any legal instrument like this is something like a gimmick.

[W]e’ve been using the term gimmick and that sometimes has negative connotations, and I’m down for reclaiming that term, but how about we replace it just for now with the word “ritual” or the word “theater,” or even the word “liturgy.”More broadly, as Grey noted in 2019:

...If you think about the way the Olympic flame gets run into the stadium, it’s this big moment, and it’s usually some culturally important figure.

I could give a child the trillion dollar coin and ask them to walk [it over] to the [Federal Reserve] and say, “Hey, we’re doing this on behalf of every child who needs to get paid.”

You can’t imagine a child pressing a button to sell the Treasury auction bid to a series of primary dealers at an interest rate that fits the spread between the repo and reverse repo rate that the Fed has set.

...[A]nother way to frame that point is...[dismissing the platinum coin for being "just an accounting gimmick"] is what an insecure person’s idea of what sophistication sounds like.

...[T]he idea there is: I can’t possibly sign off on this as a judgment call.

I need to rely on some external validation and some external reference to buttress this, unless it’s seen as being so obvious, like 'water is wet' – do you have a citation for that?!?

I think that that’s one of the elements here.

The idea [of #MintTheCoin] is that we actually have public legal authority, we have the public power of the purse and the coin’s value is just because we say so[.]

[I]n other words, its value is established by] fiat.

[And people often respond:] “Well, no, do you have a central bank balance sheet, do you have a primary dealer that’s bought this, do you have evidence that the future cash flow discounted by net present inflation expectations is gonna be sufficient? Blah, blah, blah."

No. I don’t need that citation.

The coin is its own citation. And that’s all we need.

...[T]o go back to this idea of liturgy, there’s one kind of liturgy that tells children these priests are 12 feet tall and they’re in communion with God, and they’re basically living representatives of God and this church is 80 feet high because it’s supposed to be something you’re afraid of and in or of.

And don’t you dare question us when we’re standing on the pulpit, telling you want to do.

And then there’s another kind of church that says, like a primary school classroom, we’re gonna sit on the floor cross legged because I’m the same size as a child and we’re all talking to each other as equals in a circle.

And if you want to speak, you put your hand up and it’s your turn to speak. And then when I want to speak, it’s my turn.

It’s not that I’m the priest and I have 40 minutes [to give a sermon].

And that the cathedral is a beautiful building that we built for children to play in and learn and to play beautiful music in and that’s the point of the building.

And so, we can think about a liturgy or a ritual that is designed to empower the participants in it.

But we can also think of a liturgy that’s designed to disempower everybody but those in control.

And you don’t have to go back to Martin Luther to make that point.

I think the point of the [trillion-dollar] coin is that it radically empowers average people.

...[Right now,] even as we’re literally creating money and even as the Fed is literally entangling itself with the Treasury, we [apparently] "can’t" use the coin because to do so would show people that actually, all that complicated banking BS is unnecessary and that the power to do fiscal policy, as simple as it is, exists in something as mundane and almost-a-joke as the Mint.

Kids can go to the Mint and take a public tour and they leave with a little coin.

It’s actually something that you could imagine an eight year old going into and not...falling asleep [like they would if they met] Ben Bernanke.

[T]he rise of new financial technologies, such as mobile money, blockchain, and virtual coins, have already begun to inspire renewed public interest in the process of money creation, in the process giving new meaning to Hyman Minsky’s observation that “everyone can create money; the problem is to get it accepted.”

However ridiculous or unfathomable it may have seemed to suggest the government could simply “mint” money out of thin air in 2012, it is undeniably less so [now], when the “fintech” sector is one of the fastest growing in the entire economy, and every other venture or new product is (or at least seems to be) pitched as “something-coin” or “this-or-whatever-blockchain.”

Against this backdrop [#MintTheCoin] can be understood more broadly than as a mere accounting gimmick or exotic budgetary financing tool.

Instead, it is a doorway through which we can glimpse a fundamentally different mode of monetary politics...

[T]he prospect of minting a “trillion dollar coin” confronts the public directly with the reality of the “big monetary infinity sign in the sky,” and in doing so, forces us to collectively grapple with the economic and cultural implications of the state’s money creation power.

...[It] represents an opportunity to imaginatively reclaim the public fisc from the austere clutches of red ink, overburdened grandchildren, bond vigilantes, and empty coffers.

Furthermore, the visual imagery and physical composition of coins – small, uniform, held in a “wallet,” and adorned with U.S. government insignia – serves as a useful metaphorical complement to that of the “bank account” that dominates policy discussions of new public digital currency infrastructure.

...In the broadest sense, [#MintTheCoin] represents...a public teaching moment.

...By making the inherently social nature of money impossible to ignore, [#MintTheCoin] serves as weapon against what sociologist Jakob Feinig calls “monetary silencing,” whereby average people are:[E]xclud[ed]...from knowledge of monetary institutions and turn[ed]...into mere money users and consumers[.]As we enter the era of digital currency, creative and unconventional legal ‘gimmicks’ like [#MintTheCoin] should be embraced as imaginative catalysts that invite and challenge us to collectively develop new...budgetary practices better suited to our modern context and needs.

[P]eople whose knowledge doesn’t go beyond using a credit card, depositing a check, or knowing where to get money from a pay-day lender.

... [A]nything that comes close to a structural vision [is silenced].

4. Economics

4a. Is this "printing money"?

Yes and no.

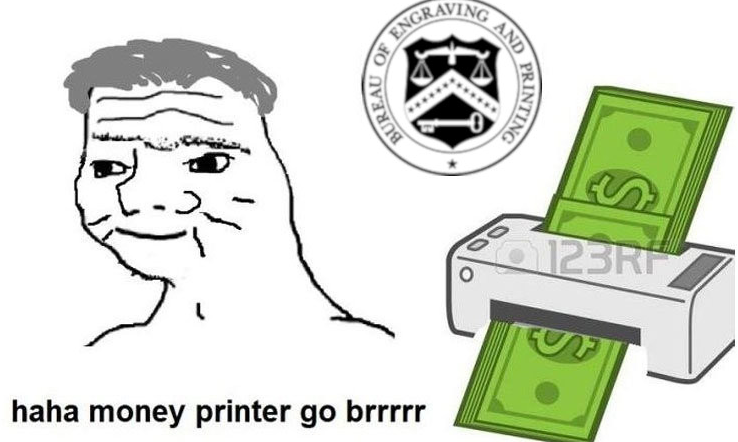

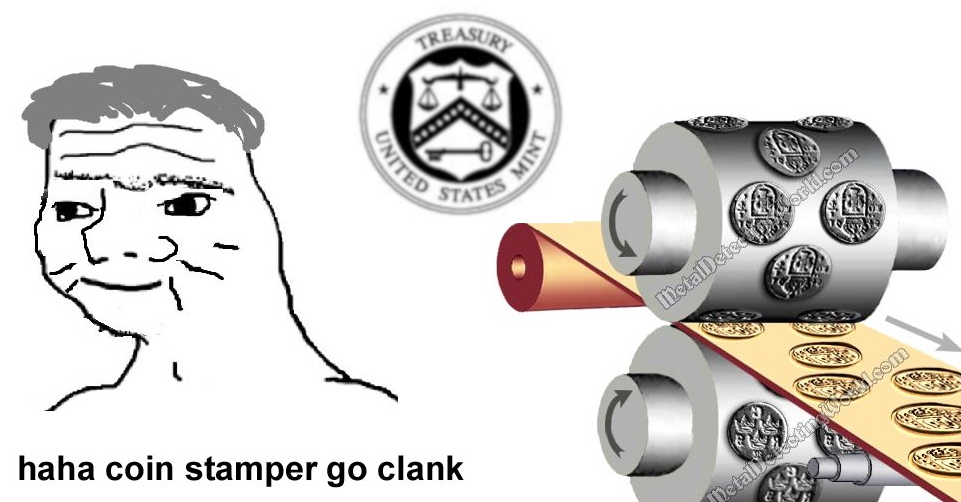

Technically speaking, the Mint "stamps" coins, whereas the entity that "prints" paper currency is the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

Or, to borrow a meme, at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing:

In contrast, at the Mint:

The Mint and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing are both sub-departments of the Treasury.

Whereas the Mint issues coins on its own behalf, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing today mostly prints paper currency on behalf of the Federal Reserve, in the form of Federal Reserve notes:

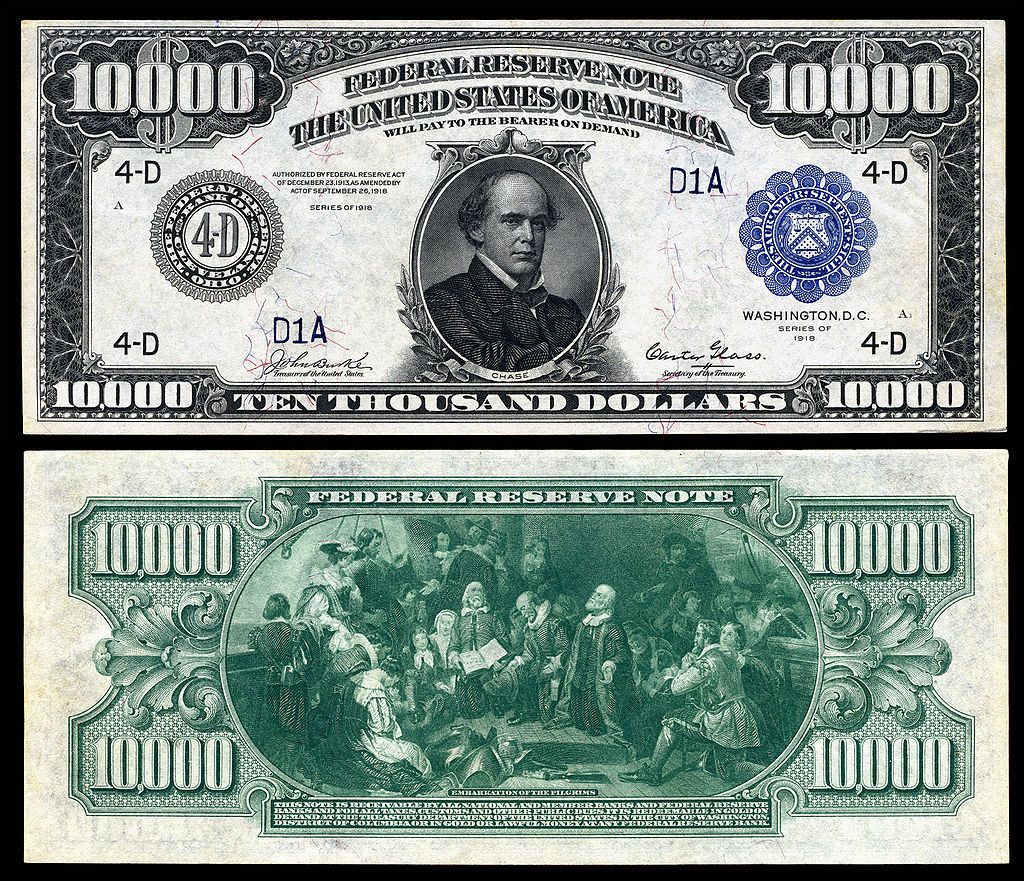

Today, the highest denomination of Federal Reserve note in active circulation is $100.

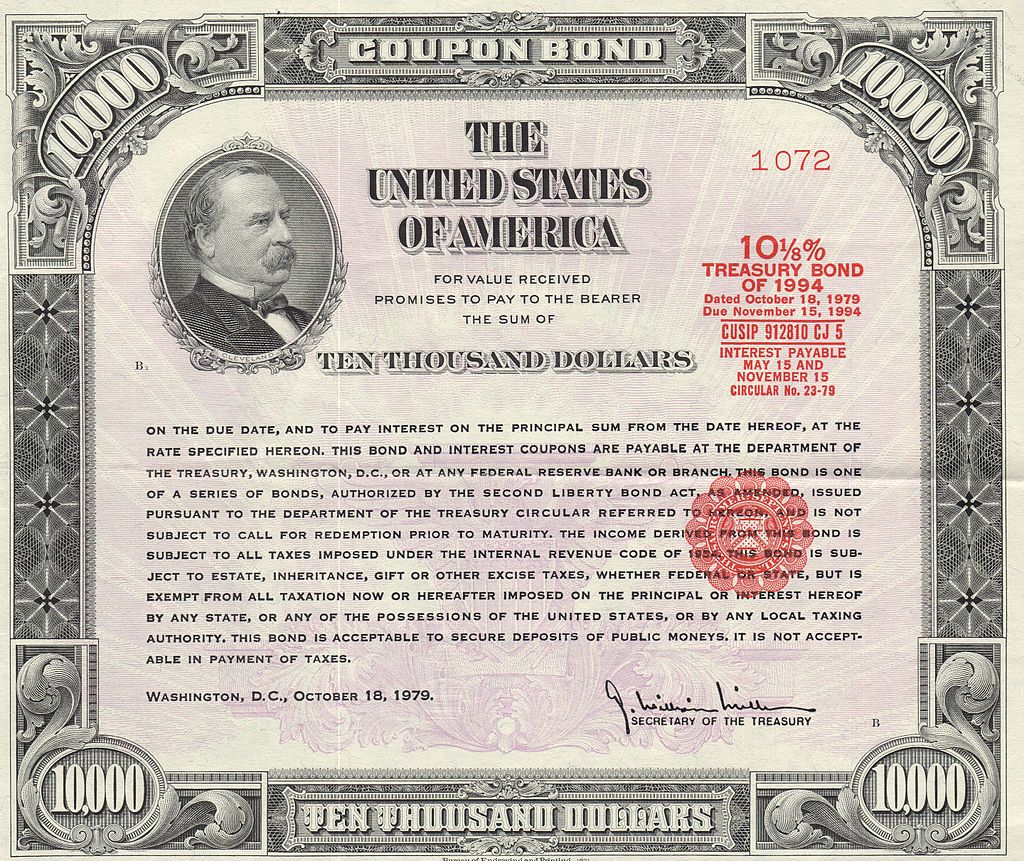

However the Federal Reserve is legally authorized to issue notes in denominations up to $10,000, and did so regularly during the twentieth century:

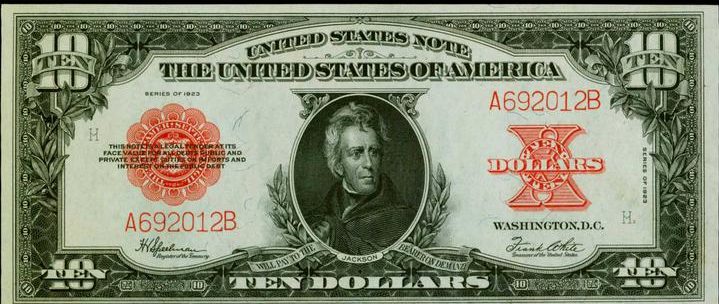

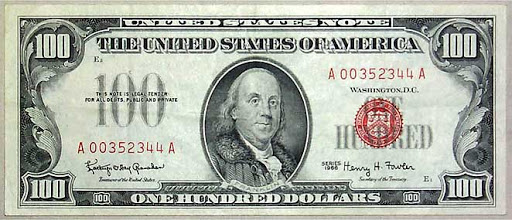

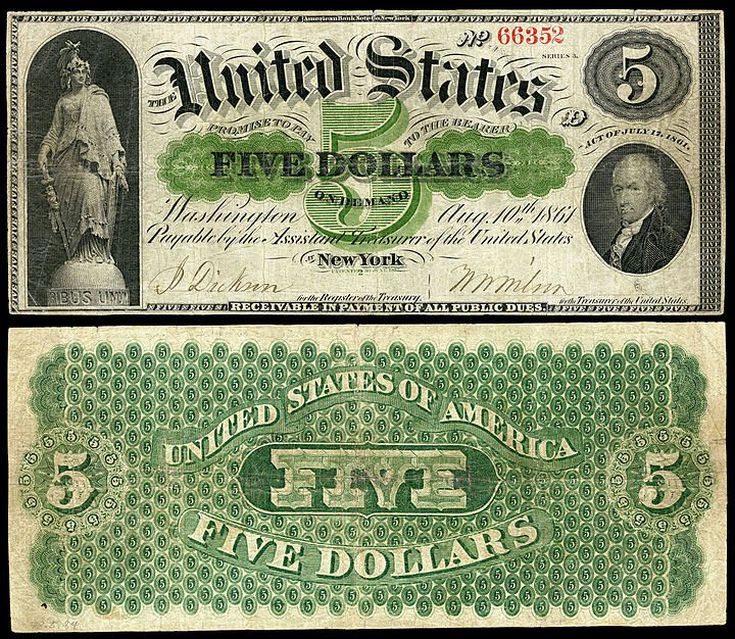

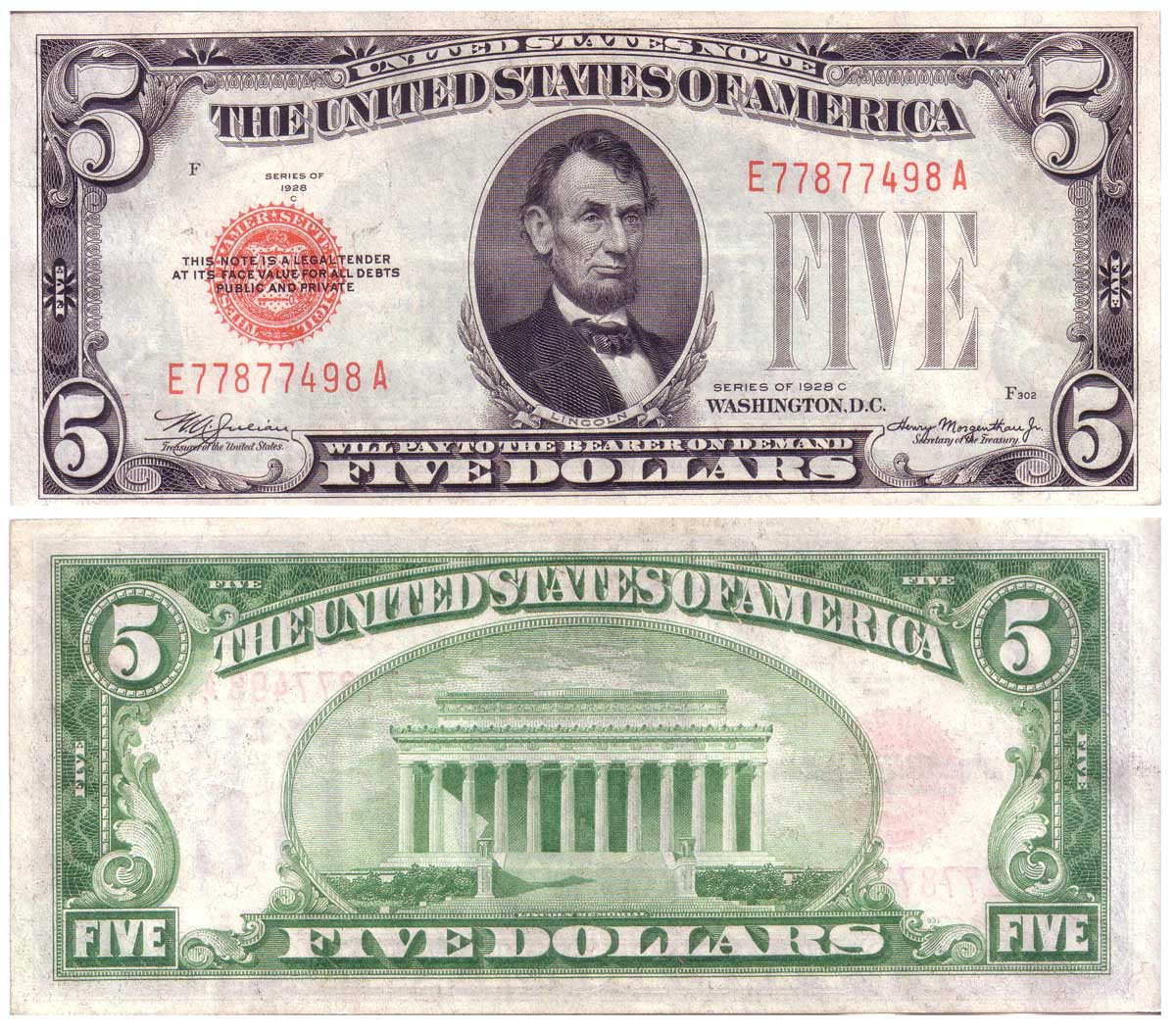

Under current law, the Treasury is also authorized to issue its own paper currency, called "United States notes":

United States notes were first introduced by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, and were known as "Greenbacks" due to the green ink used to print the back of the notes.

During the twentieth century, United States notes circulated freely alongside Federal Reserve notes, until new issuances were discontinued in 1971.

According to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, United States notes were discontinued because they "no longer served any function not already adequately met by Federal Reserve notes."

All forms of paper currency issued by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, including both United States notes and Federal Reserve notes, remain valid legal tender.

In addition, both United States notes and Federal Reserve notes are legally considered "obligations...of the United States," along with various other financial instruments issued by the Treasury, including Treasury bills;

Treasury notes;

and Treasury bonds.

Unlike Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, however, both United States notes and Federal Reserve notes are not included in calculations of public debt subject to limit under the debt ceiling (i.e. the national debt).

Moreover, while there is a $300 million cap on the amount of United States notes that may be issued - a leftover from the Civil War era, when that was a considerable amount - there is no equivalent cap on the amount of Federal Reserve notes that may be issued.

Like Federal Reserve notes, coins issued by the Mint are valid legal tender, are not included in calculations of public debt subject to limit under the debt ceiling, and are not subject to any cap on the amount that may be issued.

However, whereas the Federal Reserve Act provides that Federal Reserve notes are issued "at the discretion of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System," the Coinage Act provides that:

The Secretary of the Treasury...shall mint and issue coins...in amounts the Secretary decides are necessary to meet the needs of the United States.Today, the majority of U.S. dollars in circulation exist not in the form of coins or paper currency, but as digital account balances held in accounts at the Federal Reserve.

As the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit noted in 2019:

[Federal Reserve Banks] are the issuers of base money...they create “funds” in the most elemental sense.Furthermore, as former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke noted in 2009:

They perform this function on behalf of the United States, as federal instrumentalities...

When the Fed makes a $100 million loan to [a bank], the bank is credited with $100 million of reserves...

No preexisting “source” of funds exists...

Crediting the loan amount to the borrowing bank’s reserve account creates new reserves, increasing the overall level of reserves in the banking system by exactly the amount lent... These new reserves are created ex nihilo, at a keystroke.

[Reserves are] not tax money...According to former Chief Economist of the Senate Budget Committee (Democratic Staff), Stephanie Kelton:

We simply use the computer to mark up the size of the account.

Most people simply aren’t aware that the [Federal Reserve] doles out money using nothing more than a computer...From an economic perspective, all public money is best understood as an obligation, liability, or debt of the issuing government, in the sense that the government promises to accept it back in payment of taxes or debts owed to it.

It does this not just in an emergency but each and every day.

As British diplomat Alfred Mitchell-Innes noted in 1913:

By issuing a coin, the government has incurred a liability towards its possessor...that is to say, [it has incurred] an obligation to provide a credit by taxation or otherwise for the redemption of the coin and thus enable its possessor to get value for his money.Conversely, modern Treasury debt securities - which today exist as digital account entries at the Federal Reserve - are best understood as a special form of public money itself.

... A priceless gem or a worthless bit of paper may equally be a token of debt, so long as the receiver knows what it stands for and the giver acknowledges his obligation to take it back in payment of a debt due.

As Thomas Edison observed in 1921:

If our nation can issue a dollar bond, it can issue a dollar bill. The element that makes the bond good makes the bill good also...Indeed, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis made a similar observation in 2011:

It is absurd to say that our country can issue $30,000,000 in bonds and not $30,000,000 in currency. Both are promises to pay...If the currency issued by the Government were no good, then the bonds issued would be no good either...

If the Government issues bonds, the brokers will sell them. The bonds will be negotiable: they will be considered as gilt-edged paper. Why? Because the Government is behind them, but who is behind the Government? The people.

Therefore it is the people who constitute the basis of Government credit.

As the sole manufacturer of dollars, whose debt is denominated in dollars, the U.S. government can never become insolvent, i.e., unable to pay its bills.Furthermore, as economist Paul Krugman noted in 2013:

In this sense, the government is not dependent on credit markets to remain operational.

Moreover, there will always be a market for U.S. government debt at home because the U.S. government has the only means of creating risk-free dollar-denominated assets.

[When interest rates on short-term debt and money are identical,] issuing short-term debt and just ‘printing money’...are completely equivalent in their effect, so even huge increases in the monetary base...aren’t inflationary at all.Thus, as Willamette Law Professor Rohan Grey noted in 2019:

[F]or monetarily sovereign nations like the United States, the act of issuing government-backed securities [public debt], denominated in the domestic unit of account, which can be redeemed only for other government obligations [currency] also denominated in that unit of account, is functionally closer to “money creation” than it is to “borrowing.”Or, as British economist John Maynard Keynes noted in 1937:

This view is further supported by the fact that the Fed regularly adjusts the relative stock of circulating government securities vis-a-vis its own reserve liabilities as it deems appropriate for the conduct of monetary policy, without concern for one being “money” and the other being “debt.”

[Moreover, the Treasury and Fed coordinate closely to ensure that the private sector has sufficient reserves to purchase any and all Treasury securities offered at auction.]

...[M]ost people don’t get a loan from a bank by walking in and handing them a bag of cash so that the bank can lend it right back to them.

[W]e can draw the line between “money” and “debts” at whatever point is most convenient for handling a particular problem.Hence, as Kelton & Economics Professor Scott Fullwiler noted in 2013:

For example, we can treat as money any command over general purchasing power which the owner has not parted with for a period in excess of three months, and as debt what cannot be recovered for a longer period than this[.]

...[O]r we can substitute for “three months” one month or three days or three hours or any other period; or we can exclude from money whatever is not legal tender on the spot.

It is often convenient in practice to include in money...even such instruments as...treasury bills.

[T]he main advantage of [money-financed fiscal policy] is not that it provides a greater boost to the monetary base but that it would relieve the government from the practice of selling bonds altogether.Moreover, while the United States government is the only issuer of legal tender, it is not the only entity capable of creating "money" in the broader sense.

In other words, the main advantages of direct money creation are political rather than economic.

As Kelton (née Bell) noted in 1998:

There is an entire hierarchy of monies, which differ in their degree of acceptability...Consequently, a 'complete' understanding of 'money creation' in the modern economy must take into account "shadow money" created by other non-bank institutions lower in the hierarchy.

The simplified hierarchy can be envisioned as a four-tier pyramid, with the debts of households, firms, banks and the state each representing a single tier...

All of the money in the hierarchy represents an existing relationsihp between a creditor and a debtor, but the more generally acceptable debts [monies] will be situated higher within the hierarchy.

As the Treasury Department's Office of Financial Research noted in 2014:

[T]he monetary aggregates (M0, M1, M2, etc.) and the Financial Accounts of the United States...do not adequately reflect the institutional realities of the modern financial ecosystem...

In reality, the demarcation between money and money-like claims is not firm...

[M]oney exists along a spectrum.

4b. Is this hyperinflationary?

No.

Inflation is defined as:

A general increase in prices in an economy and consequent fall in the purchasing value of money.Inflation rates are widely believed to be determined by the total quantity of money in circulation, with large increases in the money supply inevitably resulting in hyperinflation.

This is mistaken.

When central banks purchase already-existing financial instruments with newly created money, for example, it tends to have a limited effect on inflation, since it merely involves "swapping" one asset for another.

This dynamic has been clearly observed over the past two decades in Japan.

As Hideyuki Sano and Tomo Uetake noted in Reuters in 2018:

The 553.6 trillion yen ($4.87 trillion) of assets the Bank of Japan holds are worth more than five times the world’s most valuable company Apple Inc[.] and 25 times the market capitalisation of Japan’s most valuable company Toyota Motor Corp[.]Similarly, money-financed fiscal spending is not inherently more inflationary than any other form of fiscal spending.

They’re also bigger than the combined GDPs of five emerging markets — Turkey, Argentina, South Africa, India and Indonesia...

The [Bank of Japan] has become the world’s second central bank after the Swiss National Bank and the first among Group of Seven countries to own a pool of assets bigger than the economy it is trying to stimulate.

[T]he aggressive asset purchases in recent years now mean the [Bank of Japan] owns about 45 percent of the 1 quadrillion yen Japanese government bond (JGB) market...

While some analysts credit its unique policies with lifting the economy out of decades of deflationary pressures, the [Bank of Japan] has had little success meeting its two percent inflation target or reviving domestic demand and growth.

As economist Paul Krugman noted in the New York Times in 2013:

[When the interest rate on Treasury bills and reserves is the same,] issuing short-term debt and just ‘printing money’...are completely equivalent in their effect, so even huge increases in the monetary base...aren’t inflationary at all.On the other hand, it is widely accepted that increasing demand beyond the level of goods and services available for sale can produce inflation.

As former Chief Economist for the Senate Budget Committee (Democratic Staff), Stephanie Kelton noted in 2017:

[T]he government really could give everyone a pony — and a chicken and car...so long as we could breed enough ponies and chickens and manufacture enough cars.In extreme cases, a large, sustained imbalance between total purchasing power and total productive capacity can lead to hyperinflation.

The cars and the food have to come from somewhere; the money is conjured out of thin air, more or less.

...If you need proof...look no further than the Senate’s recent $700-billion defense authorization.

Without raising a dime from the rest of us, the Senate quietly approved an $80-billion annual increase, or more than enough money to make 4-year public colleges and universities tuition-free.

And just where did the government get the money to do that? It authorized it into existence.

Whoa, cowboy! Are you telling me that the government can just make money appear out of nowhere, like magic?

Absolutely. Congress has special powers: It’s the patent-holder on the U.S. dollar. No one else is legally allowed to create it.

This means that Congress can always afford the pony because it can always create the money to pay for it.

Now, that doesn’t mean the government can buy absolutely anything it wants in absolutely any quantity at absolutely any speed. (Say, a pony for each of the 320 million men, women and children in the United States, by tomorrow.)

That’s because our economy has internal limits.

If the government tries to buy too much of something, it will drive up prices as the economy struggles to keep up with the demand.

However, as Cullen Roche noted in Business Insider in 2012:

[H]yperinflation is more than just a monetary phenomenon (and misunderstanding this led to many incorrect hyperinflation predictions in the USA in recent years).Indeed, as Felix Salmon noted in Reuters in 2012:

...[H]yperinflations tended to occur around the follow events:

- Collapse in production

- Rampant government corruption

- Loss of a war

- Regime change or regime collapse

- Ceding of monetary sovereignty generally via a pegged currency or foreign denominated debt

These events usually lead to a collapse in the tax system or expansion in deficits that appear like the cause of the hyperinflation when the reality is that the...increase [in public debt or monetary base] is always the result of some rare or extreme exogenous event.

And let’s be clear – when we say “rare” we mean really rare.

As in wars that destroy countries, regime changes that shift entire countries, corruption that destroys an economy, ceding of monetary sovereignty in the use of a currency peg or foreign debts, or a collapse in production.

[I]f your country has hyperinflation, it almost certainly has even bigger other problems.For example, as Jim Edwards and Theron Mohamed noted in Business Insider in March:

In fact, I’d hesitate to categorize hyperinflation as a narrowly economic phenomenon at all, as opposed to simply being a symptom of much bigger failures at the geopolitical level.

Those failures are exacerbated by hyperinflation, of course: there’s very much a vicious cycle in these episodes.

But you only ever find hyperinflation under extreme conditions.

In Macroeconomics 101 classes everyone learns about the collapse of the Zimbabwe economy in the late 1990s and mid 2000s, when Robert Mugabe's regime printed ever-more Zimbabwean dollars.Outside of extreme situations, economy-wide inflation dynamics tend to be poorly understood and undertheorized.

In Zimbabwe, the initial trigger of hyperinflation was clear-cut.

Mugabe forced white farmers off their land and gave their farms to the soldiers who had fought to gain Zimbabwe's independence from Britain.

The problem was these soldiers were not very good at farming. Production declined suddenly.

Estimates vary, but Zimbabwe went from being the food-exporting "bread-basket of Africa" to a nation that was unable to feed itself in a matter of months.

Agriculture was the backbone of the economy but Mugabe "destroyed in a very short time about 60% of the production capacity," according to Bill Mitchell, a professor of economics at University of Newcastle, Australia...

"Of course if you keep spending and you can't produce goods to meet that spending you'll get inflation, and if you keep spending on top of that you'll get hyperinflation," he says.

Something similar happened during the Weimar Republic, when the German government, in defeat after World War 1, printed money to pay its bills.

Hyperinflation set in and people needed wheelbarrows full of cash just to buy loaves of bread.

The war had destroyed Germany's productive capacity. But the Allies were insisting it pay reparations far in excess of the ability of the shattered German economy to pay.

So the government printed money. When a lack of productive supply met an excess demand from cash, then hyperinflation was the result.

As Harvard Law professor and former Governor of the Federal Reserve, Daniel Tarullo, noted in 2017:

The [inflation] predictions that members [of the Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve System] make about the near (or nearish) future rest substantially on a range of data that is impractical to measure directly and on a range of parameters that cannot be observed at all...On one hand, empirical evidence suggests that price dynamics in key sectors tend to drive general inflation dynamics.

After eight years at the Fed (actually, well before that) my conclusion was that there is no well-elaborated and empirically grounded theory that explains contemporary inflation dynamics in a way useful to real-time policymaking.

As Jon Sindreu noted in the Wall Street Journal in 2017:

Before the 1980s, many economists described inflation as coming from a complex mix of sources.On the other hand, the standard Consumer Price Index, which tracks price changes in a specific basket of consumer goods and services, offers limited insight into broader price dynamics across the economy.

Companies nudged up prices when their input costs were higher — “cost-push” inflation — or when shelves were depleted by booming sales — ”demand-pull” inflation...

Yet, historically, a better guide to inflation has been prices of raw materials, largely commodities.

Swings in oil markets and market expectations of long-term inflation have moved in lockstep.

Arend Kapteyn, chief economist of UBS’s investment bank, calculates that 84% of the variation in inflation since 2002 is explained by shifts in oil and food prices...

Demand may play a small role indeed in fueling inflation.

Research finds that businesses rarely price their products based on how much they are able to sell.

Rather, companies pass on to consumers as much of their costs as competition will allow.

Throughout history, most sudden spikes in inflation were preceded by rising commodity prices pushing up costs.

But even costs are complicated to measure.

Wages aren’t negotiated in the smooth manner economists imagine, because power dynamics between employers and employees can shift.

A globalized workforce, weaker unions and changing government policy likely play strong roles in keeping prices down.

Analysts and investors are paying closer attention to indicators like corporate margins and the amount of industry concentration.

Fatter profits allow companies to respond to rising commodity and labor costs without increasing prices, but a position of monopoly can lead them to pass on costs to consumers regardless.

As Sindreu noted in the Wall Street Journal in 2019:

Since the 1990s, prices have risen at totally different rates depending on the sector, official data shows.Consequently, as Nathan Tankus noted in 2017:

Education and medical care have more than doubled in cost, whereas the prices of furnishings, apparel and communication devices have fallen, thanks to cost benefits in production and advances in technology.

Without a single macroeconomic phenomenon driving all prices, trying to gauge whether an economy is running too hot or too cold based on a weighted average of these measures seems pointless.

The basic problem is that, in the post-1980s globalized economy, prices don’t move together most of the time, data shows.

[P]rices do sometimes jump simultaneously...A squeeze in oil supply in the 1970s pushed up energy prices and triggered true inflationary spirals because unions across all sectors had enough power to push for wages to increase at the same pace.

[However,] [i]n most situations, changes in prices have little to do with monetary or fiscal stimulus and need to be understood sector by sector.

Since there is no unitary force moving "general prices" in contradistinction to relative prices, there is no unitary value of money.Furthermore, while all new spending generates new income, not all new income leads to an increase in demand for goods and services.

There is only a range of things you can buy at different prices.

Why then do we persist in treating Consumer Price indices as fundamental?

So the consumer price index grew 3 per cent faster, so what?

Does that say something about the value of money in general or did 6 industries increase their target profit margins?

Income that is invested, used to pay down debts, or passively saved - for example, under the mattress - may exert little if any pressure on consumer prices.

Hence, depending on the context, injecting more money into the economy may have little, if any, effect on overall levels of demand.

At the same time, there is nothing uniquely inflationary about demand created via fiscal spending compared to any other source of purchasing power.

As L. Randall Wray noted in 2012:

[C]ash registers do not discriminate: they do not care whether that dollar comes from government spending or private spending.Indeed, government spending isn't even the primary source of new money creation in the economy.

If something is in scarce supply, more purchases of it by either government or private buyers might push up the price.

As the Bank of England noted in 2014:

In the modern economy, most money takes the form of bank deposits. But how those bank deposits are created is often misunderstood...Moreover, as the Treasury Department's Office of Financial Research noted in 2014:

[One common misconception is that banks act simply as intermediaries, lending out the deposits that savers place with them.

In this view deposits are typically ‘created’ by the saving decisions of households, and banks then ‘lend out’ those existing deposits to borrowers[.]]

[...In reality,] the principal way [that deposits are created] is through commercial banks making loans.

Whenever a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a matching deposit in the borrower’s bank account, thereby creating new money.

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks[.]

Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.

In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank money ‘multiplied up’ into more loans and deposits....

In reality, neither are reserves a binding constraint on lending, nor does the central bank fix the amount of reserves that are available.

As with the relationship between deposits and loans, the relationship between reserves and loans typically operates in the reverse way to that described in some economics textbooks.

Banks first decide how much to lend depending on the profitable lending opportunities available to them — which will, crucially, depend on the interest rate set by the Bank of England.

It is these lending decisions that determine how many bank deposits are created by the banking system.

The amount of bank deposits in turn influences how much central bank money banks want to hold in reserve (to meet withdrawals by the public, make payments to other banks, or meet regulatory liquidity requirements), which is then, in normal times, supplied on demand by the Bank of England....

For this reason, some economists have referred to bank deposits as ‘fountain pen money’, created at the stroke of bankers’ pens when they approve loans.

[T]he monetary aggregates (M0, M1, M2, etc.) and the Financial Accounts of the United States...do not adequately reflect the institutional realities of the modern financial ecosystem...There is little reason to believe the #ABCAct's emergence relief program in particular would generate significant demand-driven inflation.

[In particular,] [t]he monetary aggregates, used mainly to inform the aggregate demand management aspects of monetary policy, do not include the instruments that [financial] asset managers use as money...

There are four core institutions engaged in the issuance of money claims in the modern financial ecosystem: the central bank, banks[,] dealer banks and money market funds.

These institutions issue four core types of money claims:

These instruments have one common attribute, which is that they promise to trade at par on demand. This makes them money...

- The central bank issues reserves.

- Banks issue deposits.

- Dealer banks issue [repurchase agreements, or "repos"].

- Money funds issue constant net asset value (NAV) shares....

In reality, the demarcation between money and money-like claims is not firm...

[M]oney exists along a spectrum.

Presently, millions of people are experiencing or will soon experience a loss in income as a result of job loss or other economic disruption.

At the same time, they still have financial obligations and daily living expenses.

Without emergency relief, many face the prospect of homelessness and an inability to pay for essentials, including food and healthcare.

Additionally, the general demand slump caused by social distancing in response to the COVID-19 pandemic is self-reinforcing, as the initial decline in consumer spending results in fewer sales, which leads to more businesses shutting down and laying off workers, which leads to further reductions in consumer spending.

Consequently, the major risk at the present moment is not inflation but deflation, resulting from an overly weak economy combined with dim prospects for a quick rebound or recovery.

At the same time, there is a real risk of price pressure in certain sectors as a result of result of intentional crisis-profiteering and price gouging by price-setting firms.

As Scott Fullwiler, Rohan Grey, and Nathan Tankus noted in the Financial Times in 2019:

Whether it's businesses raising profit margins or passing on costs, or it’s Wall Street speculating on commodities or houses, there are a range of sources of inflation that aren’t caused by the general state of demand...Or, as Brendan Greeley noted in the Financial Times in 2019:

[I]f inflation is rising because large corporations have decided to use their pricing power to increase profit margins at the expense of the public, reducing demand may not be the most appropriate tool...

[Instead,] we need alternative tools in place to manage the power of big business and ensure their pricing policies are consistent with public purpose.

[I]t's possible that price stability isn't just the Fed's mandate, but also the mandate of the Department of Justice and the Federal Communications Commission.

[In 2017. then-Chairwoman of the Federal Reserve] Janet Yellen said a drop in mobile phone prices was one of several "transitory" or "one-off" factors keeping inflation down...

At the time, [we] focused on the word "transitory," and thought it was a bit of a punt.

We might have been wrong.

In late 2011, the [Department of Justice] and then the [Federal Communications Commission] both signaled disapproval of AT&T's $39b plan to buy T-Mobile, and then AT&T gave up the deal.

It was a surprise to most people watching; after a decade of mergers, telecoms had gotten used to getting what they asked from Washington.

T-Mobile's parent company, Deutsche Telekom, had been desperate to get out of the US wireless market, and AT&T had been so confident the deal would go through that they offered break-up terms: $3bn, and even more important, spectrum.

All of a sudden, Deutsche Telekom couldn't get out of the US market, and so with cash and spectrum, decided to make a competitive wireless carrier. Very competitive...

To pick up customer share, T-Mobile...cut both prices and terms, and the rest of the industry had to follow.

...So when Janet Yellen noted what she called a "one-off," "transitory" move in the price of wireless service in 2017, a move that she said was part of what was holding down inflation, she was looking back at five years of newly aggressive antitrust policy from the [Department of Justice] and the [Federal Communications Commission].

Antitrust policy then became monetary policy.

It lowered inflation.

4c. If we can do this, why not give everyone unlimited money?

The fact that Congress has the power to "coin money" and "provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States" does not imply that any and all exercises of those powers are equally valid or desirable.

Similarly, the fact that the government does not have a intrinsic financial budget constraint does not imply that it can spend without limit and not face any negative consequences.

Instead, it implies that the limit on government spending is determined by productive capacity and real resource constraints, not a scarcity of money at the Treasury.

In this instance, coin seigniorage is being used only to honor spending commitments that have already been incurred. To the extent there are (valid) concerns about the merits of some of the spending that has been appropriated by Congress, such issues can and must be addressed through the budget proces itself.

4d. If we can do this, why tax at all?

Taxation plays a critical role in establishing the value of public money.

As Pavlina Tcherneva notes:

Economists, numismatists, sociologists and anthropologists alike have long probed the vexing question 'What is money?'At an administrative level, taxation is a valuable tool of public policy.

...Among them are advocates of an approach identified as 'Chartalism[.]'

...[T]he Chartalist contribution turns on the recognition that money cannot be appropriately studied in isolation from the powers of the state - be it modern nation-states or ancient governing bodies.

It thus offers a view diametrically opposed to that of orthodox theory, where money spontaneously emerges as a medium of exchange from the attempts of enterprising individuals to minimize the transaction costs of barter.

The standard story deems money to be neutral - a veil, a simple medium of exchange, which lubricates markets and derives its value from its metallic content.

Chartalism, on the other hand, posits that money (broadly speaking) is a unit of account, designated by a public authority for the codification of social debt obligations.

More specifically, in the modern world, this debt relation is between the population and the nation-state in the form of a tax liability.

Thus money is a creature of the state and a tax credit for extinguishing this debt.

If money is to be considered a veil at all, it is a veil of the historically specific nature of these debt relationships.

... It is a well-established fact that money-predated minting [coins] by nearly 3000 years.

Thus Chartalists aim to correct a common error of conflating the origins of money with the origins of coinage[.]

Very generally, [Chartalists] advance two accounts of money's origins.

[The first account] posit[s] that money originated in ancient penal systems which instituted compensation schedules of fines...as a means of settling one's debt for inflicted wrongdoing to the injured party.

These debts were settled according to a complex system of disbursements, which were eventually centralized into payments to the state for crimes.

Subsequently, the public authority added various other fines, dues, fees and taxes to the list of compulsory obligations of the population.

The second account...traces the origins of money to the [ancient] Mesopotamian temples and palaces, which developed an elaborate system of internal accounting of credits and debts.

These large public institutions played a key role in establishing a general unit of account and store of value (initially for internal record keeping but also for administering prices).

...[M]oney evolved through public institutions as standardized weight, independently from the practice of injury payments.

These stories are not mutually exclusive...since a system of debts for social transgressions existed in pre-Mesopotamian societies, it is highly likely that the calculation of social obligations was transformed into a means of measuring the equivalencies between commodities.

...In Egypt, as in Mesopotamia, money emerged from the necessity of the ruling class to maintain accounts of agricultural crops and accumulated surpluses, but it also served as a means of accounting for payment of levies, foreign tribute, and tribal obligations to the kings and priests.

As Beardsley Ruml, then President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, noted in 1945:

The United States is a national state...whose currency...is not convertible into any commodity.

It follows that our Federal Government has final freedom from the money market in meeting its financial requirements.

Accordingly, the inevitably social and economic consequences of any and all taxes have now become the prime consideration in the imposition of taxes.

In general, it may be said that since all taxes have consequences of a social and economic character, the government should look to these consequences in formulating its tax policy.

All federal taxes must meet the test of public policy and practical effect.

The public purpose which is served should never be obscured in a tax program under the mask of raising revenue.

Federal taxes can be made to serve four principle purposes of a social and economic character.

These purposes are:...In serving these purposes, the tax program is a means to an end.

- As an instrument of fiscal policy to help stabilize the purchasing power of the dollar;

- To express public policy in the distribution of wealth and income, as in the case of the progressive income and estate taxes;

- To express public policy in subsidizing or in penalizing various industries and economic groups;

- To isolate and assess directly the costs of certain national benefits, such as as highways and social security.

The purposes themselves are matters of basic national policy which should be established, in the first instance, independently of any national tax program.

Among the policy questions with which we have to deal are these:These questions are not tax questions; they are questions as to the kind of country we want and the kind of life we want to lead.

- Do we want a dollar with reasonably stable purchasing power over the years?

- Do we want greater equality of wealth and of income than would result from economic forces working alone?

- Do we want to subsidize certain industries and certain economic groups?

- Do we want the beneficiaries of certain federal activities to be aware of what they cost?

The tax program should be a means to an agreed end.

The tax program should be devised as an instrument, and it should be judged by how well it serves its purpose.

5. Institutional Politics

5a. Is this monetary policy?

No.

The Treasury Secretary is merely using their existing legal authority to honor spending commitments that have been legislated by Congress, in a manner that is also consistent with other, Congressionally-imposed limits on the issuance of public debt subject to limit under 31 U.S.C. § 3101. It is not a replacement or substitute for monetary policy operations conducted by the Federal Reserve.

Nor does it share the primary objective of monetary policy, which is to:

[P]romote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.Moreover, using high value coin seigniorage to avoid a catastrophic and unconstitutional default does not undermine Federal Reserve independence.

5b. What role does the Federal Reserve play?

12 U.S.C. § 391 provides that:

Federal reserve banks...when required by the Secretary of the Treasury, shall act as fiscal agents of the United States.Similarly, 12 U.S.C. § 391a provides that:

[T]here are appropriated such sums as may be necessary to reimburse Federal Reserve Banks in their capacity as depositaries and fiscal agents for the United States for all services required or directed by the Secretary of the Treasury to be performed by such banks on behalf of the Treasury or other Federal agencies.Consequently, it is the Federal Reserve's legal responsibility, as the Treasury's fiscal agent, to facilitate both depository and spending functions carried out by the Treasury on behalf of the United States government, which in thise case involves accepting coins presented by the Mint for acquisition and deposit at the direction of the Treasury Secretary.

Upon purchase, the Federal Reserve credits the Mint's operating account at the Federal Reserve with reserve balances in an amount equivalent to the full face value of the coins.

The Federal Reserve then retains permanent ownership of the coins.

The Federal Reserve may, at its discretion, choose to pay interest on any reserve balances created as a byproduct of purchasing coins in accordance with the Treasury's directives.

5c. What does the Federal Reserve do with the coins?

Coins issued by the U.S. Mint are legal tender, and consequently are booked as an asset on the Federal Reserve's balance sheet at their nominal face value.

The Federal Reserve may retain permanent ownership over any and all high value coins purchased under this approach. Alternatively, it could sell it to private actors, transfer ownership to other government entities, or, when appropriate, return them to the Mint to be struck down.

5d. Does this affect Federal Reserve remittances to the Treasury?

Yes.

In the event that the Federal Reserve acquires coins that pay zero interest, while choosing to continue to pay a positive interest rate, this will result in reduced net operating profits available for remittance to the Treasury. However, any reduction in income experienced by Treasury as a result can be more than offset by the seigniorage revenue generated by the initial issuance of the coins.

5e. Does this undermine Federal Reserve independence?

No.

The purpose of this process is to allow the Treasury to honor Congressionally-mandated spending commitments without engaging in knowingly unconstitutional behavior.

The Federal Reserve's involvement is limited to the acquisition and retention of platinum coins issued by the Mint on behalf of the Treasury.

In this respect, the Federal Reserve is merely fullfilling its statutory obligation as the Treasury's fiscal agent, a function that it has performed continuously since its founding in 1913.

Any economic and political effects of the program remain the sole responsibility of Congress and the Treasury.

Furthermore, coins are legal tender, and are booked as an asset on the Federal Reserve's balance sheet at their full face value.

Consequently, any and all newly created Federal Reserve balances remain fully capitalized by the coin assets held on its balance sheet.

6. Strategy

6a. Is it better to issue one big coin, or multiple smaller denomination coins?

Issuing a single coin gives the impression that this is something that can and should be done only once.

In contrast, issuing multiple coins establishes a precedent - practically and psychologically - for issuing additional coins in the future, if and when circumstances warrant it.

6b. Why not issue more coins, even outside of debt ceiling crises?

There is nothing preventing Congress from directing the Treasury to use coin seigniorage more prominently in regular budgetary operations, or to retire existing public debt.

.

6c. Why is this better than alternative ways of avoiding budgetary crises, like invoking the 14th Amendment as a justification for ignoring the debt ceiling limit entirely?

High value coin seigniorage is politically and operationally superior to other alternatives for multiple reasons, and does not carry any greater risk of inflation.

First, coin seigniorage serves a pedagogical function by challenging the popular myth that in order for the Treasury to spend, it must first collect tax revenue or "borrow" from the bond market or foreign investors.

Second, separating fiscal spending from the management of government securities markets allows policymakers at Treasury and the Fed to simplify and streamline both processes, which are currently convoluted and inefficient. This could be achieved, for example, by authorizing the Federal Reserve to issue its own safe, liquid securities, which, as Nathan Tankus has argued, would also improve its ability to implement monetary policy.

6d. Isn't public debt good?

In a floating exchange rate, fiat currency regime, public debt does not serve any meaningful fiscal or budgetary function.

However, Treasury securities do currently play an important role in the Federal Reserve's implementation of monetary policy.

As Nathan Tankus notes:

In the United States, for the past 80 years at least, the main asset that monetary policy has been focused on in its purchase and sale policy are treasury securities.In 1949, the Congressional Joint Committee on the Economic Report published a report titled "A Collection of Statements Submitted to the Subcommittee on Monetary, Credit, and Fiscal Policies by Government Officials, Bankers, Economists, and Others."

What is overlooked about this fact is another simple fact- the Federal Reserve does not issue this financial instrument.

...In other words, the Federal Reserve doesn’t control the most basic element of its purchase and sale policy.

Thus, for all the talk of central bank independence, day to day operations are a result of close cooperation between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury.